1-1: Why Containers?

1-1: Why Containers?

"Works on My Machine"

So you're a software developer, and you're creating a web application for multiple clients. This thing has several front-end and back-end dependencies, many of which are version-sensitive. You've targeted specific versions of these dependencies based on your needs, but these are not the newest around.

The application also relies on a database which in turn has version-specific dependencies. You've made certain that the app runs smoothly in the intended environment, but here's the trick: how can you guarantee that the production environment your clients will deploy is what you've promised will work?

Traditionally, the answer would be to deploy the application in a virtual machine, and provide the VM image to clients, guaranteeing the end user's deployment mirrors the developer's. This is essentially shipping "Works on my machine" as a service.

So what's the problem?

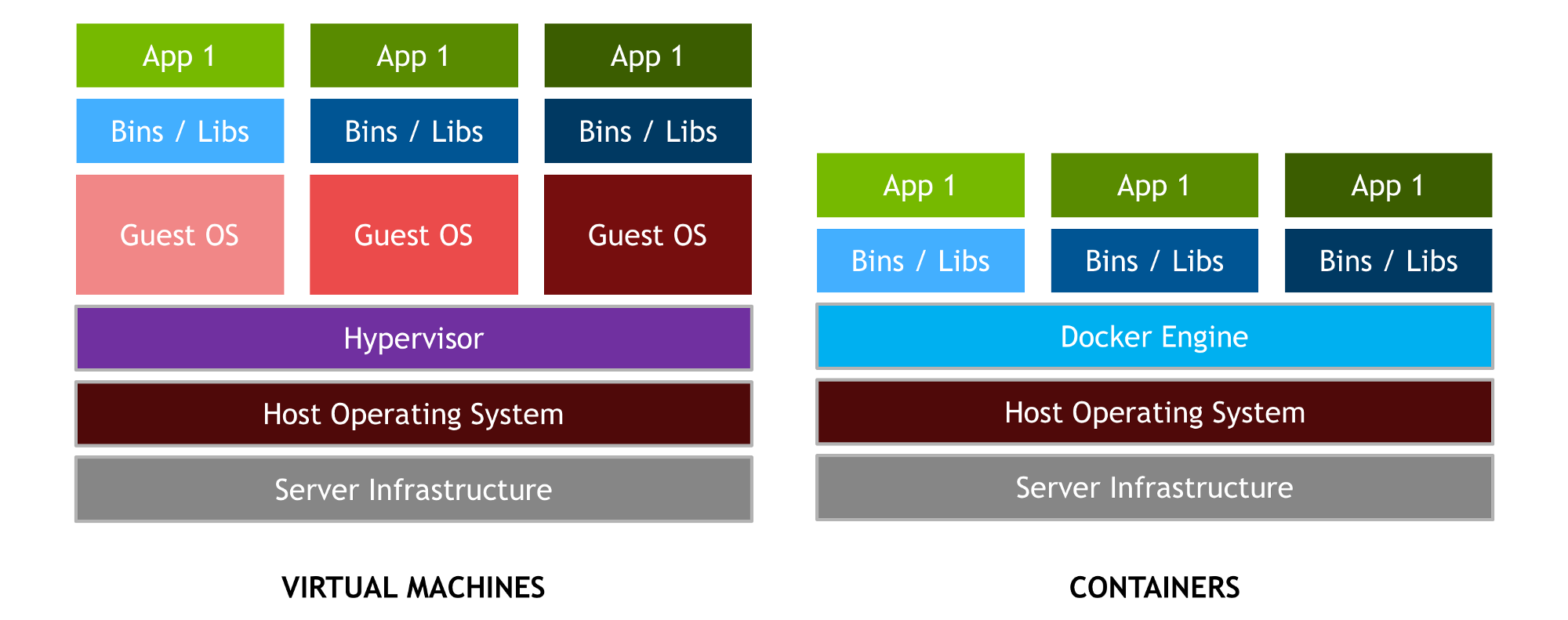

For one thing, VMs come with a lot of excess baggage. Each virtual machine is a completely emulated hardware set and operating system, on top of which we add the application and its dependencies. If we imagine several applications like ours, that's a lot of redundancy!

Source: Devopedia

Enabling Patching

And what happens when our users update that VM as part of routine and appropriate patching? Will they be forced to update the dependencies our app relies on, before we're ready to update our app to use the new version? Our users should keep their VMs patched, and our software's requirements should not stand in the way of that objective.

What if we could use a single operating system, but then isolate multiple applications and their dependencies, sharing what could be shared, and keeping isolated what shouldn't be?

That's what containers do. We're able to ship our app and dependencies without the overhead of a full virtual machine. Each container is a predictable environment we can provide to users, who can deploy easily and with confidence that the app will work "out of the box." What's more, the host machine for these containers can be updated as normal without impacting the operation of the containerized application.

Sane Deployment Targets

Let's talk about that "box" we ship to users. Published software can take all kinds of different shapes, from .msi installer packages to tarballs of source code. Each has benefits and drawbacks, as do containers.

For developers, containers represent a sane deployment target—put another way, a sensible endpoint in the software development pipeline. Container technologies also tend to integrate well with continuous integration/continuous deployment (CI/CD) tools, making containers even easier to target as a final product.

For consumers/users, containers represent a standard deployment mechanism: learn how to use containers, and you'll be able to reasonably deploy a wide array of applications in the same way, on the same infrastructure.

Bad Reasons for Containers

If you noticed that no form of the word "secure" has appeared in this explanation, well done; that's entirely intentional. By themselves, containers are not a security control. Thinking of them as such is courting disaster. Between misconfigurations, container escape techniques, and simple application requirements, the "isolation" afforded by containers is by no means a firewall, or even an impenetrable sandbox for your code. They can be made more secure (or less), but that's about hardening the solution. It is not itself a security solution.

Nor do containers obviate the need for vulnerability management! It'd be all too easy to say "No more need to patch; our app and dependencies are sandboxed!" Nothing could be further from the truth. If anything, shipping containerized applications obliges developers and maintainers to take stronger security measures with their products, because containerized software often eludes traditional vulnerability management. As we'll describe later, it's important to consider what a secure development pipeline looks like. Once again, containers are not by themselves a security control.

Containers, or Docker?

Hopefully I've made a compelling argument for the benefits of containerized applications. Most folks who have heard of containerization have probably heard of Docker, the most common container implementation. But Docker is just one instance of a specification defined by the Open Container Initiative. So why focus on it?

Prevalence and familiarity, mostly. Although other container technologies exist—and we'll eventually discuss them in this course—Docker is unquestionably the most prevalent, and the easiest to get started with. So yes, we'll be using Docker, that sometimes-annoying, sometimes-maligned, first-mover-advantage-haver in the container space. But through this single tool, we'll explore broader container concepts that can apply to all implementations of the OCI specification.

Okay, now that we've justified this course's very existence, let's get our environment set up.